“People have to have hope that their lives can be different. And hope is not a cheap religiosity that some divine intervention can change this – it’s a union job, it’s more than a living wage, it is capped rent, it’s parks, it’s library, it’s healthcare.”

Before Karl Barth took an academic post and wrote Church Dogmatics he pastored in the town of Safenwil where the town’s economy revolved around two textile factories in which workers labored for 12 hours a day earning barely enough to eat. Only six months after his arrival Barth realized that “shrugging one’s shoulders over taking a conscious position on practical matters…absolutely doesn’t work for a pastor.” He began to teach on labor policy and invited other pastors to consider social issues in the community. He became known as The Red Pastor of Safenwil.

Looking back on that time, Barth wrote:

In the class difference that I saw concretely before me in my congregation, I was touched for the first time by the real problems of real life. The result was that for some year…my only theological work was reduced to the preparation of sermons and classes which I still did quite carefully. What I really studied were factory acts, insurance business and trade unionism and the like, and my attention was claimed by violent local and cantonal struggles, which were cause by my taking positions on behalf of the workers.[1]

Jesus was a worker and so were the factory workers in his congregation. Jesus’ ministry was to the poor and oppressed and here were the poor and oppressed. Barth concluded that the good news was a material reality that made material demands.

I’m thinking about this intersection of real-world problems and theological concerns with renewed vigor as we are fast approaching a new Trump era. And in that vein, I’m thinking about the statements faith communities make to clarify and organize their resistance against tyranny.

Not long before the election, I noticed that a group of evangelical leaders published a statement called “Our Confession of Evangelical Conviction.” It contains veiled references to Trump, though he is not named in the document: “We reject the stoking of fears and the use of threats as an illegitimate form of godly motivation, and we repudiate the use of violence to achieve political goals as incongruent with the way of Christ.”

At other times the writers dig into theological commitment. They give their allegiance to Christ alone. They value every person as made in God’s image. It has the feel of the Barmen Declaration. No ideology and politics, just theological truth around which we can organize our lives.

Confessions like these have a “stand the test of time” feel to them, and there’s a lot to appreciate about a sustained witness that remains unchanged regardless of the state of the world. “Preach as if nothing happened” Barth told the Confessing Church preachers as he was exiled from Germany – but we also know how that worked out.

At the same time, I’m in a tradition that frequently and intentionally shifts our confessions of faith to respond to new questions before us. One of the exercises I give to our new church member class is to look at three different versions of Mennonite confessions of faith to see if they can imagine how particular historical events shaped the theology of the church at that time. In the Schleitheim Confession, Anabaptists are clear about their non-participation in government affairs:

Shall one be a magistrate if one should be chosen as such? The answer is as follows: They wished to make Christ king, but He fled and did not view it as the arrangement of His Father. We shall do as He did.

By 1963 this section of the confessions look different: “In law enforcement the state does not and cannot operate on the nonresistant principles of Christ's kingdom.” A new question arrived, perhaps inspired by the images plastered across television screens of cops using firehoses on Civil Right. Should Mennonites participate in policing? No Mennonite cops in 1963! (To our detriment, the language falls out of in 1995 where we see positive language that leaves the interpretive door open: We may participate in government or other institutions of society only in ways that do not violate the love and holiness taught by Christ and do not compromise our loyalty to Christ.)

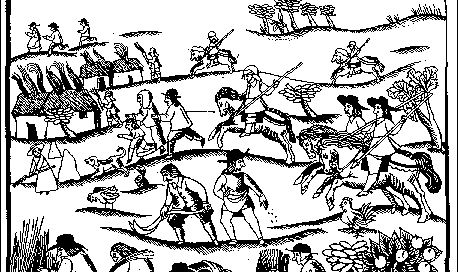

I like these pointed and practical theological declarations about our material condition. They offer clarity and urgency in times of upheaval. This week I went back and read Thomas Müntzer’s “Fundamental and Just Articles of all the Peasantry and Tenants of the Spiritual and Temporal Lords, by Whom They Consider Themselves Oppressed.” I wanted to root myself in the kind of confession that emerges when Scripture is read through the eyes of the working class.

While Müntzer’s turn towards armed rebellion through the Peasants’ War has led many in my tradition to distance Müntzer from Anabaptism, I think of him as one of our people. His interpretation of Scripture finds its end in firm and present political realities, for instance, a form of taxation called the small tithe. He explains his reason for rejecting this tax in the articles: “And we will not pay the small tithe at all, for the Lord God created cattle free for Man’s use; we consider it to be an unjust tithe which has been invented by men. Therefore we will not pay it any more.” God does not execute a tax on human use of creation and neither should the state/church. Müntzer takes a theological reality – the use of creation – and derives a political commitment.

In confronting feudalism’s enslavement, atonement provides the conditions for freedom – rather than subject to arbitrary feudal lords the people are subject to God’s laws. Müntzer condemns “how the lords treat us as property” because “Christ redeemed us all by shedding his precious blood, regardless of whether it is a lowly shepherd or the highest in the land, with no exceptions.” Does this mean they are not to be obedient to these lords? No, but in contrast to deference by rank, we ought to “humble ourselves before everyone.” The universal character of redemption forms a way of life, a politics.

I spoke at a church a few weeks ago, a church working out its post-evangelical identity. At the end, someone asked about the first steps to activating congregational life towards justice. How do they pick the issue they want to work on? The best I could offer was to try doing what Jesus told us to do. Get people out of prison. Feed people who are hungry. Collectively organize your property and money. Pronounce woe upon the rich. That seemed like a good place to start, and this is the place I pastor from.

I got the sense that my biblical literalism surprised some in the audience. After all, they’d spent a lot of time deconstructing their biblical literalism to arrive at a more temperate and open theological vision. I was suggesting they go backward! I suppose that’s correct. Many of the most interesting political theologies I know emerge from centuries of close biblical alignment, and often these forms of life were horrifically repressed by the state-church. Anabaptists believed, literally, that Jesus’ command to love our enemies required us not to kill. The Diggers occupied the Commons because they took seriously that all the believers in Jerusalem held common property. Quakers opposed slavery because Jesus’ redemption unites all people in kinship. It might have done the Confessing Church well to simply say, as Mennonites do, that we do not swear oaths to anyone, including Hitler, because we let our yes be our yes and our no be our no.

What does our reading of Scripture say about labor organizing? About each person having access to housing? How can we move from “welcoming the stranger” to a rejection of the Trump administration’s campaign of mass deportation?

At this moment, we need robust and materialist theological imaginations. Consistently, these imaginations develop not in attempts at theological unity across broad spectrums of often incompatible theologies (see Barth’s chilling analysis of the Confessing church --“The Lutheran Church slept and the Reformed Church kept awake”) but through people who live within communities of people for whom the good news of Jesus was written. Perhaps more than a new Barmen Declaration we need Fundamental and Just Articles of all the Peasantry and Tenants of the Spiritual and Temporal Lords.

(In other news, I’ve migrated to BlueSky, @melissaf-b.bksy.social) - hope to see you there!)

[1] Tietz, Christiane, '“The Red Pastor”: Safenwil, 1911‒21', in Victoria J. Barnett (ed.), Karl Barth: A Life in Conflict (Oxford, 2021; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 May 2021).

I wish I had more to say than "thank you." But thank you. There is a lot to think about here, and to ponder how to put into practice.

So good. Love the idea of walking through some of the ways church confessions have changed over time in response to current events. Making those connections and reinforcing the idea that we keep developing our theology and practice as we go, and that's a good thing...