Towards No Future

Anti-abortion's existential crisis, reproductive futures, and climate pessimism

Politics are getting weird for the pro-life movement after the Dobbs decision that put an end to the constitutional right to an abortion, placing reproductive health decisions in the hands of state legislatures made up of straight, white men and triggering dozens of abortion bans across the country. Over and over, for decades, we have heard the same conviction echo through the Republican party’s anti-abortion agenda: life begins at conception and any attempt to end that life by human intervention is equivalent to murder and should be treated as such in a court of law.

You would imagine that Republicans would cheer the recent ruling from the Alabama Supreme Court, effectively ending the practice of embryo creation, storage, and destruction in the process of in vitro fertilization. After all, by the logic that brought us to Dobbs, an embryo is a person at conception, whether in a petri dish or a womb. As such, embryo destruction, either by a medical intervention or through biomedical disposal constitutes murder.

Instead, within days of the ruling, the GOP issued talking points telling their people to show unequivocal support for IVF. It only took a week for the Alabama legislature to enshrine protections for providers against prosecution in the case of embryos being damaged or destroyed. This is, as you can imagine, creating a quandary for anti-abortion activists. There are hundreds thousands of abandoned embryos in frozen storage right now. “Suboptimal” embryos (those carrying genetic difference) are often destroyed in the process of IVF.

There’s so much to say. We could talk about the hypocrisy of the anti-choice movement (“reproductive choice for me but not for thee”). We could look at this turn of events as a continuation of the war on poverty or trace the line of race-hate by the GOP to its logical conclusion (poor Black and brown women are those who primarily seek abortions while overwhelmingly wealthy white women – the GOP constituency – utilize advanced reproductive technologies).

I’ve read articles this past week about the “shock” experienced by Republican women when it comes to the controversy of IVF. Over and over the sentiment comes to this – we are trying to create families, to produce futures, to have more life in the world. That is the line separates IVF from abortion, and always has. At the end of the day, the logic of personhood is a specter. What conservative want is the proliferation of the family, of the child, by whatever means necessary.

After seeing this unfold in real time, I went back to Lee Edelman’s book No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive as a way to interrogate what is happening, what lies beyond personhood claims. Edelman theorizes the politics of reproductive futurism. In this reading, The Child represents the sacrifices we make for the future, the world we are willing to inhabit for a reality that is not yet come into being. By always imagining hospitable futures, we abandon the possibilities of the here and now.

Edelman is not talking about real children, because reproductive futurism has no space for the agency of actual future children.

The image of the Child, not to be confused with the lived experiences of any historical children, serves to regulate political discourse - to prescribe what will count as political discourse - by compelling such discourse to accede in advance to the reality of a collective future whose figurative status we are never permitted to acknowledge or address.

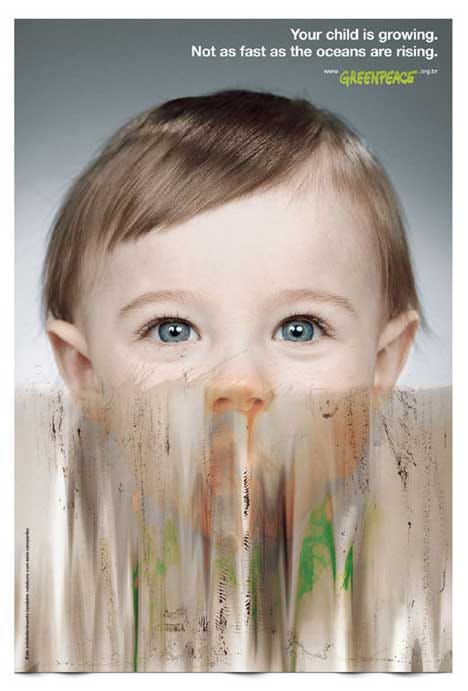

The terror of the future of The Child requires us to be chained to a politics of incremental and non-disruptive change that prizes repetition of the same. This is, of course, a feature of right-wing politics – as we’ve seen in throughout the abortion wars of the past decades. Republicans are deeply invested in fictive children but when these children materialize into flesh and blood, they face onslaught of death-dealing policies from the same ideological wing. The price of electing anti-abortion judges was ceding all other considerations for human thriving (clean water, housing, education, access to food). All life is sacred until that life is in the electric chair.

But this reproductive naturalism also finds its way into left-leaning political regimes, particularly in the politics of climate change. Think of Taylor Swift’s craven appeal to buying carbon offsets to render her private jet fleet carbon neutral. Or the praise by Saudi Arabia for a “flexible approach” to a fossil fuel recalibration. Or the expansion of EV technologies that require mining for minerals on Indigenous sacred land instead of a reinvention of cities for carless futures.

We get all of this instead of a radical upheaval of our economics, a revisioning of the very form of life we have come to expect as normative. We continue to act as if there is a future constituted within the same economic and social forms we currently inhabit.

But there is no future.

Abandoning reproductive futurism is not giving up. The alternative exists in pre-colonial systemic change that come in the form of intentional economic slowdown and deindustrialization. I’ve recently come across The Habak: Majority World Survivalism Project that seeks to prepare the global community with self-sufficiency practices. I’m looking to organizations like A Growing Culture. We can look towards Afrofuturism as a set of practices to chart paths for our present. This will require invention, imagination, and creation – but for the now, for the child who is already among us, who is us.

I think there’s work here for Christian theology which is, in many ways, also attentive to a death drive. One of four primary commitments is to apocalypse, to no future. “Keep awake, therefore; for you know not the day or hour.” In my circles, the politics of this orientation is either a rejection of this world in favor of a perfected future (a non-reproductive futurism) or a liberal rejection of the apocalypse in favor of an ethic of “God making all things new,” which is a way to say “things are going to get better.” This is categorically untrue and has led towards significant climate anxiety. Again, there is no future for our current present.

I’m interested in Christian theology, particularly eco-theology that will engage in its own interrogation of reliance on a politics of reproductive futures. Our Christian pessimism is a source of hope for the kinds of radical realignments that are before us.

Could a faithful Christian place hope in a future of "God making all things new" while also keeping our eyes on the here and now, remaining committed to the kind of radical societal reorientation you speak of here?

This is a book! One I’m desperate to read.