“He is the Breast of Life, and the Breath of Life; the dead suck from His life and revive.” Ephrem the Syrian, Hymns on the Nativity (Hymn 3)

Ephrem’s hymns, written in Syriac in the 4th century, are among my favorite theological explorations of Christ’s divinity, humanity, and gender. Interspersed in the hymns, Ephrem loops back on Mary’s experience, presenting Jesus in a woman’s body.

Though Most High, yet He sucked the milk of Mary, and of His goodness all creatures suck! He is the Breast of Life, and the Breath of Life; the dead suck from His life and revive.

We learn that, as Jesus suckled from Mary, he was simultaneously a nursing mother, “suckling all with Life.” Ephrem repeats this pattern with the womb.

He was wholly with all things and wholly with each. While His body was forming within the womb, His power was fashioning all members! While the Conception of the Son was fashioning in the womb, He Himself was fashioning babes in the womb.

Jesus has a womb, even as he is inside a womb, Mary’s womb the nesting place for his womb where “He was fashioning babes.” Rather than the body Christ, and therefore the body of God, as essentially male, Ephrem images Jesus as a woman.

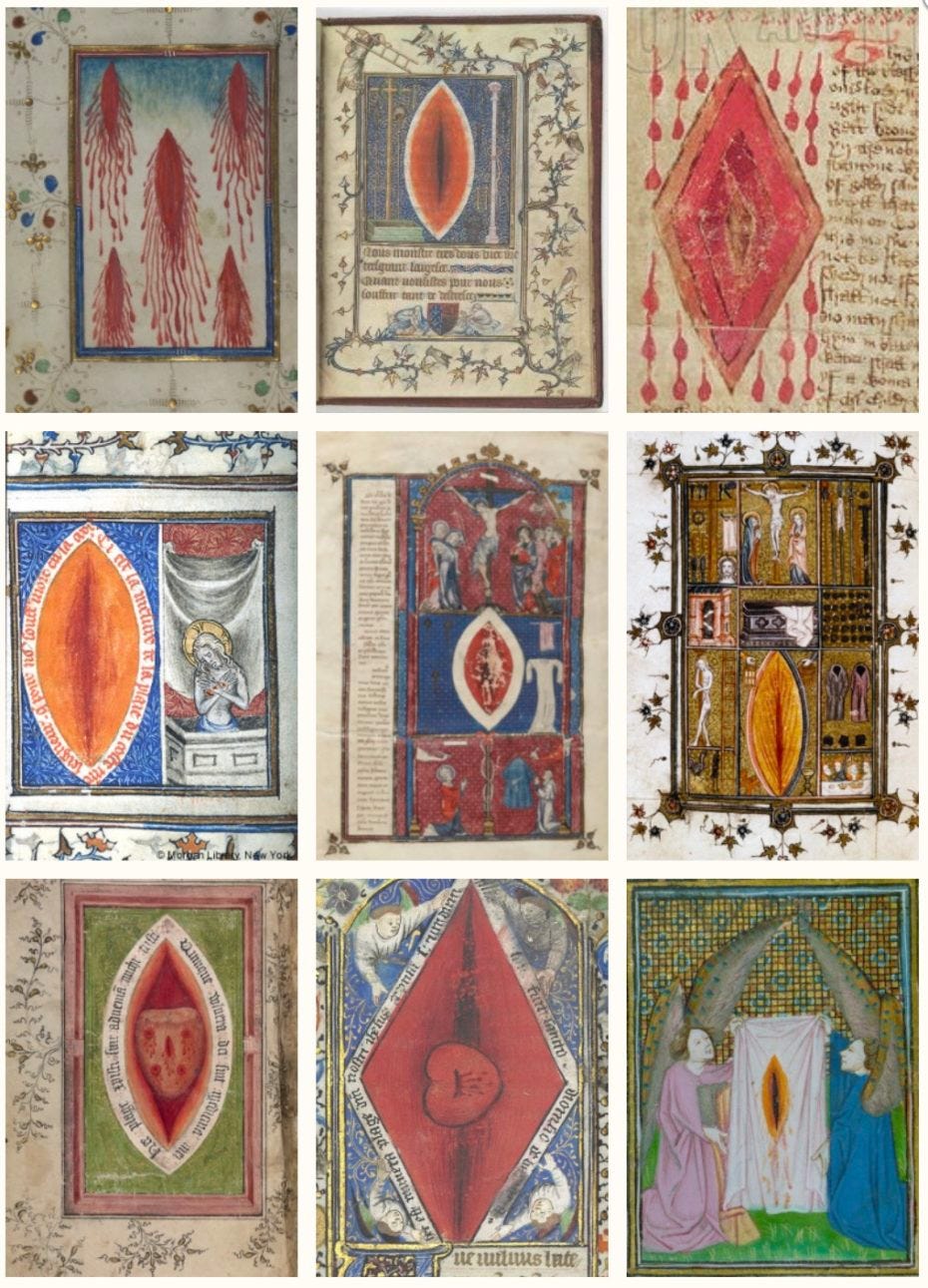

Ephrem isn’t alone in construing Jesus with a woman’s body. The fifth wound of Jesus was a popular image in Medieval Christian art. The first four wounds are left by the nails in Jesus’ hands and feet. The fifth wound is caused by the spear that pierces his side, from which “blood and water” pour out.

Over time that gash in this side took on a life of it’s own in prayer books and devotions like The Book of Hours. The wound became detached from the body, rotated sideways and took on a mandal shape. There is no sign of trauma and no blood. The wound is independent of the body that bears it.

Caroline Bynum (in her magisterial essay on the side wound) describes how Augustine shows the roots of this bloodless wound when he describes how the soldier “opened” the wound in Christ’s side, “truly just as a door or window is opened, so this soldier opened for us the spiritual door through which the sacraments of the church flow, without which no one enters into true life.”

Bynum writes,

When the author of the Expositio describes the door in Christ’s side as opening to emit the church and the sacraments of blood and water, that opening seems natural rather than artificially inflicted. Such language (aperire, emanare) tends to identify it with female rather than male bleeding. In the Middle Ages (in spiritual, medical, and romance literature alike) woman’s bleeding (in birthing and menstruation) was understood to be from natural orifices, men’s was from orifices made by unnatural breaching.1

The images of the side wound are visually feminine - they resemble a vulva. At times this connection was made explicit. “Not only did they resemble the vulva visually,” writes Sophie Sexton, “they were used to prevent pains associated with the vagina. Birthing girdles often carried depictions of the side wound and were pressed against women in labour to help with the pain of childbirth. The images could also be pressed against women to help with period pain.” But veneration and devotion to the side wound was not exclusively maternal. These images were kissing and rubbed.

We find the imagery of both Jesus and Paul as mother in Anselm’s writings:

But you, Jesus, good lord, are you not also a mother? Are you not that mother who, like a hen, collects her chickens under her wings? Truly, master, you are a mother. For what others have conceived and given birth to, they have received from you... You are the author, others are the ministers. It is then you, above all, Lord God, who are mother.

Bernard takes up this language but almost exclusively through the image of Jesus as breastfeeding babies. This imagery also applied to the abbot who suckles those in his charge with wisdom and care — even as he continues to refer to the abbot as “father.”

At the same time, both Anselm and Bernard retain gender essentialism in their portrayals of Jesus, Paul, and the abbott. Fathers are disciplinarians — mothers are nurturers. Both exist in the bodies of the men who are to care for the communion of saints. These images are also exclusively tied to mothering, another essentialized characteristic applied to women. We see transgressions of gendered bodies, and their reinforcement.

We discover the Jesus who plays within gender, who weaves in and out of the particularities and the gray spaces of sexed binaries, most fully in Scripture. Isaac Villegas, in his essay in the most recent issue of Worship (“Son of Man… Vindicated by Her Wounds”), walks through the biblical material of Jesus’ gender queering. Jesus refuses to settle into one side of a binary, but instead shifts between pronouns and images.

One place we witness this transgression is in Jesus’ exchange with John the Baptist, where Jesus refers to himself as “the Son of Man” and then switches to the female pronoun in the next sentence: “wisdom is vindicated by her deed” (Matt 11:19, Luke 7:35). “She is the Son of Man,” comments Villegas, “and he is Sophia.”

For centuries, the church will hold fast to another feminine self-description by Jesus, one Jesus offers in Matt 23:37 - “how often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings.” Jesus mothers the church and in takes on other mothering activities. Caroline Bynum writes, “Not only was Christ enfleshed from a woman; his own flesh did womanly things: it bled, it bled food and it gave birth” (quoted in Villegas’ article, and in Eugene Rogers’ After the Spirit, 116).

Another place we encounter the sexual transgression of Jesus’ body is on the cross, where he is mocked, stripped, and crucified naked. Several scholars’ work defines the Roman crucifixion Jesus endured as sexual violence that utilized power to gender Jesus’ body. For the Romans, biological gender was usurped by a definition of men as “the impenetrable penetrators.” Sexual norms in Roman society worked upon this binary of the one penetrated (woman) and the one penetrating (man). The stripping, beating, penetrating with a sword and nails of a male body reveals the body of the crucified as victim of sexual violence endured by female (penetrated) bodies.

As the politicized war against trans people rages across red states and in evangelical churches, we can remember that the body of Jesus refuses to settle into the masculine template assumed by this movement. From a theological vantage point this is necessary for salvation. Gregory the Theologian reminds us “that which is not assumed is not healed.”

If half of Adam fell, also half will be taken up and saved. But if all [of Adam], all of his nature will be united [to God], and all of it will be saved.

A Jesus who is essentially male can only redeem men. As it is, the Jesus who comes to us embodies the fullness of our creatureliness, imaged as God and imaged as person - “God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.”

I often remember this on the Sundays when I preside over Communion. “This is my body,” I say in Christ’s words with my body that bleeds each month, that has borne children, that has been sexualized and inappropriately touched. I say these words with Jesus’ body and as Jesus’ body, now all of us, bound up in the redemptive power of resurrection.

“Do this in remembrance of me.”

Caroline W. Bynum, “Violence Occluded: The Wound in Christ’s Side in Late Medieval Devotion” in Feud: Violence, and Practice: Essays in Medieval Studies in Honor of Stephen D. White, eds. Belle S. Tuten and Tracey L.Billado 9 (Burlington: Ashgate, 2010), 98.

Julian of Norwich also often referred to Jesus as our “Mother,” as in this one of my favorite quotes: “We make our humble complaint to our beloved Mother, and he sprinkles us with his precious blood, and makes our soul pliable and tender, and restores us to our full beauty in course of time… And then the true meaning of those lovely words will be made known to us, ‘It is all going to be all right. You will see for yourself that everything is going to be all right.’